10 years ago, The Phoenix Project took the IT world by storm. It spoke to the deep dysfunction in many teams, of a million departments blamed for when things go wrong but never credit when things go right.

The solutions it proposed also sparked a fire: that the resulting conservative approaches to change management wouldn’t help, and that the principles of Lean, Six Sigma, and Statistical Process Control could.

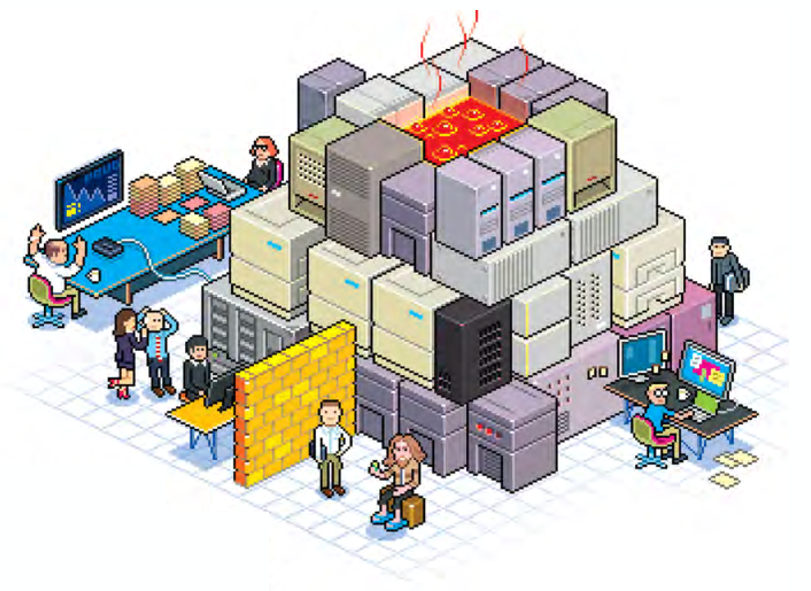

The book offered a huge insight: thought is just another work product. IT work has almost no physical aspect: there’s no inventory, no giant molds or presses, and no distribution centers. The output of IT is just thought, carefully written down. Once you consider the resulting thought as inventory or Work in Progress, you can apply the tried-and-true process engineering approaches: reducing waste, Just In Time inventory, kanbans, etc.

If you haven’t read it, I recommend. Even if you don’t work in tech, the lessons apply to similar disciplines. Marketing, Finance, HR, and Legal match the same pattern, and even services such as medical care or management consulting. Heck, it probably works for psychics and math teachers too.

The Phoenix Project categorizes work into four categories, which I’ll summarize below:

- Standard work is the work you’re paid to deliver. Maybe it’s typing out scans of handwritten doctor’s notes. Maybe it’s doing three-way matches for vendor invoices. Maybe it’s leading yoga classes.

- Project work is the effort you apply to improve standard work. Maybe you reduce the hours each delivery takes. Maybe you reduce turnaround time. Maybe you reduce the variability of a dependency.

- Customer projects are done to improve the value of what your standard work delivers. Maybe you’re adding features. Maybe you’re improving the consistency of the work product.

- Unplanned work adds no direct value. These are the fires and the emergencies that prevent you from doing the first three. The book spends a lot of time on unplanned work, explaining that you often get the most productivity gains on a team from just reducing unplanned work. I have noticed independently that unplanned work is the most tiring and demoralizing, so suspect that reducing it also makes teams happier and reduces burnout.

It Goes Deeper

After I read the Phoenix project, I started seeing work in those categories. It inspired me to change my work habits to reduce the impact unplanned work has on me and my teams. In the book, unplanned work is usually described at the team level – usually system outages (because IT). The spirit is even more subtle: unplanned work happens anytime someone says, “stop what you’re doing, please do this thing for me now.”

Unplanned work is an interruption, with all the implications about the costs of context switching. Personally, it also risks disrespect: the requester implies that their request is more important than whatever they displaced. It takes away autonomy, planning, and self-management. When most work is unplanned, you lose the ability to prioritize, will be less efficient, and most importantly, cannot optimize. That can be a dark place.

Often personal unplanned work is caused by:

- poor planning. How often is your emergency caused by someone else’s procrastination?

- people wanting special treatment. If you have a two-week backlog of standard work, people may try to jump the line and ask you directly.

- inadequate process. Perhaps people are interrupting you with requests because that’s the only way they know to ask for what they need.

The book has many solutions at the team and organizational level, and I’ll augment them with a few others I’ve learned.

- Set boundaries. If you comply with requests to skip the line, you will teach people that the line is optional. Use emergencies as an opportunity to educate people about the value of your team and their existing work: “What would you do if this didn’t get done until Friday?” or “Is your request more important than these other projects?” Lencioni had some great thoughts about how poor personal boundaries can spiral into deep dysfunction.

- Create processes. This has so many names, but the core concept is simple: figure out what your team does, then create standard processes to deliver them. Process Engineering is the subject of countless books and a consulting industry worth billions.

- Marketing. If you want people to use your process, they have to know about it and it must be easier than whatever they’ve been doing. There are many ways to achieve this and they all boil down to good marketing. You must convince people to use the intakes you’ve designed instead of bothering you. This allows you to scale: instead of triaging each problem as it comes in, you can explain up front what you do, then let them figure out how they want help. Common approaches include searchable webpages explaining your team’s services, regular presentations to potential consuming groups, and Call To Action buttons to make it easier for them to get started.

The Fifth Type of Work

A year ago, I was discussing all this with a non-IT friend. He is an Optimizer like me and was pre-convinced of all these ideas. He suggested a fifth type of work: Performative Work. Performative Work is work you do not because it benefits your customer or your team, but to improve the perceptions of the people around you.

There is a fundamental assumption in the Phoenix Project: that everyone is motivated to deliver value. This is far from true in the real world, especially at old and large companies – a lot of people don’t actually care. Maybe their priority is just pleasing people, or maybe it’s to punch a clock and do as little as possible, or maybe they want status and power. Any of these goals can yield Performative Work if culture and incentives at your organization don’t address it.

Performative Work can show up in a lot of ways: changing something just to be able to say you helped, attending meetings just to be involved, talking about how great you are, or saying positive platitudes to be thought of as a leader.

Performative Work is often unexamined; many people do it without realizing it. If you see it, recognize that it may be automatic, and approach it as a learning or growth opportunity.

Some people also have rationalized that it’s a necessary component to delivering value. To a degree, this is true: you must operate within the culture of the organization you find yourself in to succeed. Consider dress codes: if you worked at IBM in the 70s, you needed to wear a suit and tie every day (I’m generalizing to men’s dress because IBM didn’t hire a lot of women in the 70s).

There is absolutely no correlation between ability and what style of fabric is currently adorning your body. However, the culture at IBM prioritized suits so much that if you didn’t wear one, it would negatively impact your peers and bosses' perception of your competence. They would then devalue your work, effectively limiting your ability to contribute.

It’s hard to help if everything you do gets thrown away.

You can play this game with any other indicator: race, gender, accent, name, caste, and haircut have all been widely used as proxies for effectiveness, intelligence, approach, and expertise. They are all absurd but are realities of our world. If you are in a culture that associates some unrelated indicator with competence, you may need to adjust yourself to avoid barriers for your success. If you can’t, recognize that your ability at this organization is limited, it’s not reflective of your value as a person, and you should consider applying your talents somewhere else.

Note : I recognize that for some, moving is not a real choice because the associations are endemic within industries and societies. We shall overcome.

If your culture values leaders for their ability to self-promote, you may need to spend time on that, just to avoid the associated perception of incompetence which results in actual inability to add value.

An Important Exception: Sales and Marketing

Marketing and Sales educate customers about the value you offer. This is important: people won’t use you if they don’t understand why they should. Creating perceptions within customers is their primary goal, and you want to hire people talented at that. In other words, people who are good at Performative Work.

This is an old problem, and successful sales teams universally deliver by doubling down on the numbers. Sales compensation is notoriously tied to metrics: deals closed, margin on those deals, etc. They have realized that in an environment rife with self-promotion, the only way to succeed is to take away all such opportunity, and direct that talent outward to the customers.

Marketing has come late to the same place. For decades, it was difficult to gauge the performance of marketing campaigns or teams. Recent advances in data processing make accurate marketing metrics possible. This is the biggest use case for Big Data: measuring the impact of large campaigns and incremental changes to message. Ecommerce is a great example: it relies on metrics such as organic search and SEO scoring, conversion rates, average revenue per transaction, and add-on click rate. TV ad effectiveness is still hard to measure, but hard data have taken over the marketing world just like it did sales.

The Problem

The lesson is clear: even within teams dedicated to Performative Work, it is unhelpful when directed internally.

Clearly, Performative Work is a drain on an organization. It’s even worse for an organization’s efficiency than suit-wearing or sexism. Mandatory suits annoy some people and reduce your value proposition as an employer. Deep sexism will reduce your talent pool by half, probably cost you sales, and may risk negative PR.

But a culture that encourages Performative Work may waste half its combined staff resources. If you’re a typical pragmatic CFO, that’s way worse for the books than sexism. When you add in correlated risks like gut-based decisionmaking, it can be even worse.

What do we do?

The prevalence of Performative Work may be more difficult to detect in an organization than racism, but still easy individually: ask, “what value are you trying to deliver?” anytime you suspect Performative Work. If there is no meaningful answer, you’re probably right. If the answer is weak, you can usually nail it down with the followup question, “Is that the most effective way to deliver that value?” At worst, these questions can help others recognize Performative Work. At best, they may have real answers with new and useful perspectives about perceived risks or root causes. If you ask these questions with a curious tone and frame of mind, there’s no downside and substantial benefit.

If you are a leader accountable for culture, you can set and encourage patterns that reduce Performative Work. It flourishes in places where leaders:

- Value polish and executive presence

- Reward yesmen and confirming leader opinions

- discourage conflict

- devalue alternate viewpoints from subordinates

- avoid unpleasant realities

- Prioritize optics over truth

- Have a significant mismatch between what they say and what they do

Adopting the principles of Lean espoused by the Phoenix Project will reduce Performative Work. Usually, this happens by helping people focus on real priorities and metrics that reflect overall organizational success. If you’re forced to reward actual improvement, it will be harder to indulge in pleasant lies and hire people just to justify your decisions – those costs become apparent quickly and are hard to justify against objective metrics of value.

I suspect that the reverse is actually more true: that a culture of Performative Work blocks any meaningful adoption of Lean. Many businesses and organizations, attracted by the incredible advantages, embark on large Lean and Six Sigma efforts. Most fail. I suspect most fail because the key leaders that define culture are unwilling to give up their pleasant lies and confirmation bias, and that approach cascades down to everyone. Since nobody is willing to choose metrics that will expose deficiencies or prompt hard questions about value, the Lean initiative becomes a façade, going through the motions while delivering none of the value.